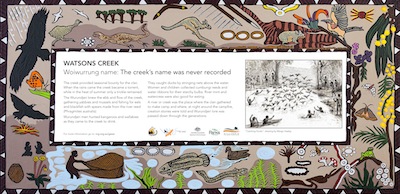

Plaque #7 WATSONS CREEK

The creek’s Woiwurrung name was never recorded.

The creek provided seasonal bounty for the clan. When the rains came the creek became a torrent, while in the heat of summer only a trickle remained.

The Wurundjeri knew the ebb and flow of the creek, gathering yabbies and mussels and fishing for eels and blackfish with spears made from the river reed (Phragmites australis).

Wurundjeri men hunted kangaroos and wallabies as they came to the creek to drink. They caught ducks by stringing nets above the water. Women and children collected cumbungi reeds and water ribbons for their starchy bulbs. River mint and watercress were also good for eating.

A river or creek was the place where the clan gathered to make camp and where, at night around the campfire, creation stories were told and Wurundjeri lore was passed down through the generations.

****************

Additional information

Water is very significant for Wurundjeri camp sites. Useful plants grew along the creek margins: the common reed (Australis phragmites) for making fishing spears; Cumbungi for starchy roots and fibrous leaves for string; river mint, water ribbons (Triglochen) bulbs, water cress for food. Blackfish, eels, yabbies, mussels, abounded. Ducks were trapped in nets strung across the river; kangaroos and wallabies were hunted as they came to drink.

Water was drawn from the river in a tarnuk. The Wurundjeri hollowed out a burl cut from a manna gum and fixed a string handle to it.

Watsons Creek was named after Sandy Watson, a farmer who sold butter and meat to the miners on nearby diggings.

Clan gatherings

When the clan arrived at the camp site, everyone had a task to perform. From those who built the willams, lit the camp fires, prepared the food, to those who would oversee the suitable socializing of men and women. The willams were arranged according to their relationship to clan heads and principal families. Uninitiated men and women did not sit at the same camp fire. When leaving the camp site, no personal rubbish was left behind, not even a strand of hair as Aboriginals believed evil spirits would use it to harm the owner. This belief meant sites were kept hygienic. Same sites were occasionally used on a seasonal basis, but with long enough intervals to allow waste materials to decompose.

Encampments were formally organised places. When the Bunurong were in Melbourne encamped with other ‘tribes’, their position in relation to the other groups was always closest to their own country, so that a diagram of the groups of their willams on the ground was an image of a birds eye view of the spatial relationship of their countries on the ground. William Thomas (Assistant Protector 1839-1849) drew a plan of this on the occasion of the greatest number of the tribes ever to be assembled in Melbourne in recorded times: 164. The occasion was the ritual spearing of two Western Port men, Billy Lonsdale and Lively over the killing at Western Port of the Wooralim boy at Mr Manton’s at Western Port.

When a clan were encamped by themselves, the encampment would have followed the general principles explained to AW Howitt by William Barak – a favourable position relative to the weather, and in many cases facing the rising sun. The relationship of willams on the ground depended on the relationship of any individual or group with the important clan heads and principal families. Thomas drew this too, from Barak’s information. Barak put himself at the centre of the diagram for illustrative purposes. He and his wife and child were number one; his brother and wife and child were number two, close to him; Barak’s father and mother were number three, double the distance away and in another direction; Barak’s wife’s mother and father were even further away in the same direction and screened from Barak’s sight; the young men’s willams were the furthest away from Barak, and lastly visitors were the same distance away from Barak as his own mother and father, but in a different direction. When Thomas camped with them, he situated his tent so that its flap or opening faced their willams.

Their pre-European pattern of living included regular congregating in what is now the city of Melbourne – all five of the Kulin nations – but for a short time only, for business and ceremony: local food resources could cope with large numbers for a short time. The arrival of the protectors with their goods and their promises, followed by the arrival of La Trobe in September 1839 attracted hundreds of the five tribes to Melbourne, expecting largesse. They stayed in the summer of 1839 for months, and came back in the spring, and they were hungry, denied access to European enclosures, forbidden to cut bark for willams for shelter, and with kangaroos scarce around what are now the suburbs of Melbourne: Thomas recorded in this period that he rode for 20 miles on the south of the Yarra and did not see one kangaroo.

Reference: “I Succeeded Once” based on the personal and official journals kept by William Thomas, Assistant Protector to the early colony and then Guardian of the Aborigines of Victoria 1849-1859.

**Special thanks to Judy Nicholson for Gawa Trail artwork**